01

About Tsai Ken 關於蔡根

About Tsai Ken 關於蔡根

⌈The distinction and harmony among materials make up the core of my works.

|

|Artist Tsai Ken (1950-) |The studio of Tsai Ken in Sanzhi

Born in Taipei in 1950, Tsai Ken graduated from the Division of Sculpture, National Taiwan Academy of Arts in 1972. He had learned human body sculpture for more than a decade. Senior sculptor Chen Hsia-Yu had rhapsodized about his works. Nevertheless, Tsai felt restricted in this subject matter. The turning point in his artistic career didn’t come until he visited the Occident in 1983.

⌈It’s hard to deny that the human body is beautiful.It’s understandable to start arts training with beautiful forms. However, what else should a work of art have besides the beauty of form?This is a question I’ve been trying to answer after years in creating human body sculptures.|Tsai Ken2⌋ |

At that time, arts education in Taiwan was deeply influenced by Western art trends. During his enrolment at the academy, Tsai studied Western catalogues in bulk and conducted in-depth analysis and research. On his travel in 1983, Tsai visited major occidental museums, and he was aware of the fact that it’s impossible to surpass the West in terms of Western culture.3 Therefore, he took a two-year hiatus from artistic creation for reorientation.

⌈I noticed that Western art has a cognitive edifice. However, I have reservations over whether it is suitable or comprehensible for an Easterner.From another angle, I was vague about the roots of my native culture, and I found no entry point. So I put aside Western art history and circumvented the intellectual expedition into Chinese art history. I tried to pursue my ideal straight from my quotidian existence, returning to the discernment of my own life.|Tsai Ken4⌋ |

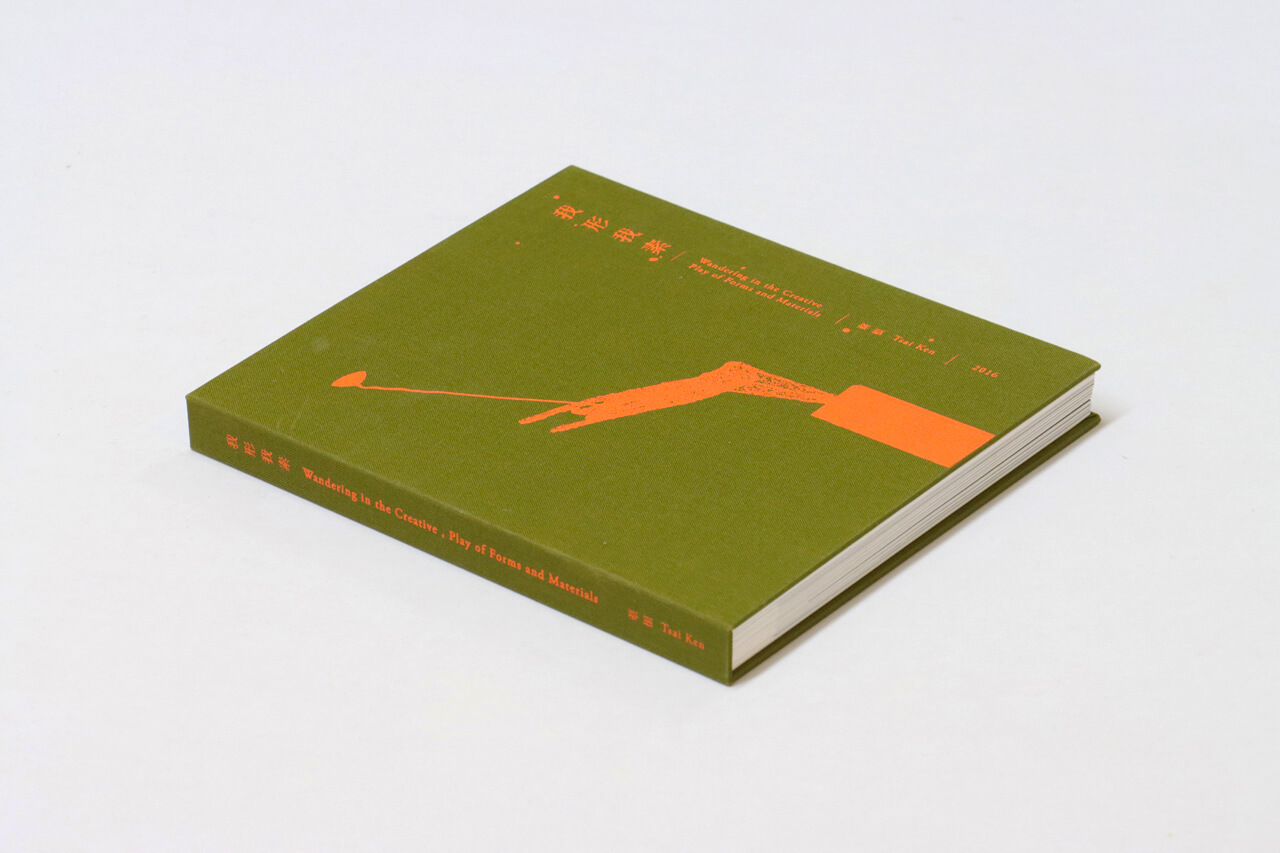

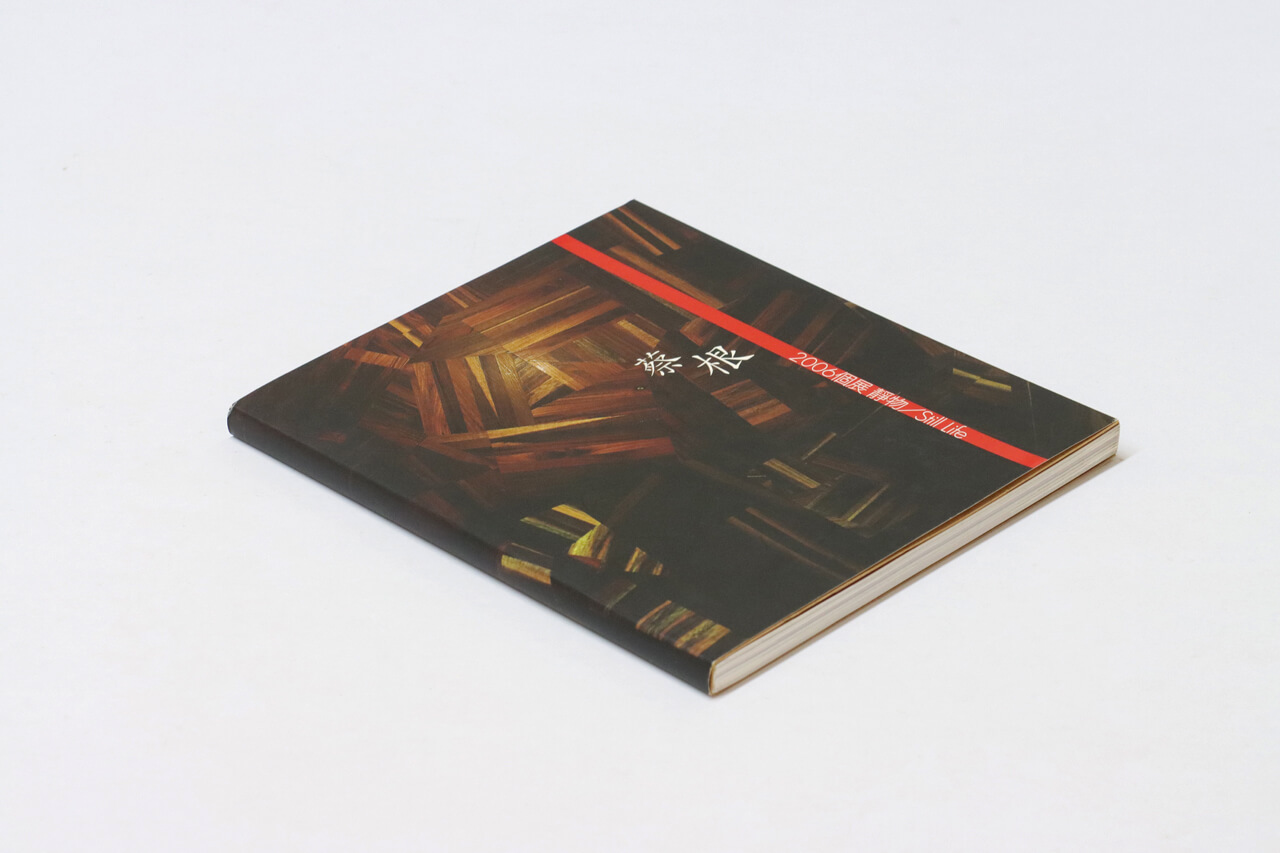

Tsai joined the faculty of National Taiwan Academy of Arts in 1985 to teach the woodwork workshop. He glued discarded wood together and carved it. This was the first material he discovered after clay modeling. Starting from plywood, Tsai added stones, wires, dead twigs, discarded furniture, and other mixed media successively. In the collecting process, he preserved the original appearance of some of the materials and put the “readymade” in his works. In his 1997 solo exhibition “Beyond the Horizon; Beyond the Form,” Tsai declared that “my work is no longer based on the result of the shape, but on the interrelationship between the materials,” which served as his most essential creative vocabulary thenceforth.

|Tsai Ken, Flying III (partial), 1997, 56x34x206cm, Mixed media

Tsai Ken, Flying III, 1997, 56x34x206cm, Mixed media

|

Treating his life experience as the point of departure, Tsai’s early solo exhibition focused on family ethics, which had many to do with the fact that Tsai was nearly 40 and took on triple roles of a son, a husband, and a father at that time. Later, Tsai’s family moved to Sanzhi, where he found the mutual testimony between nature and life amidst the mountain forest and the sea.5

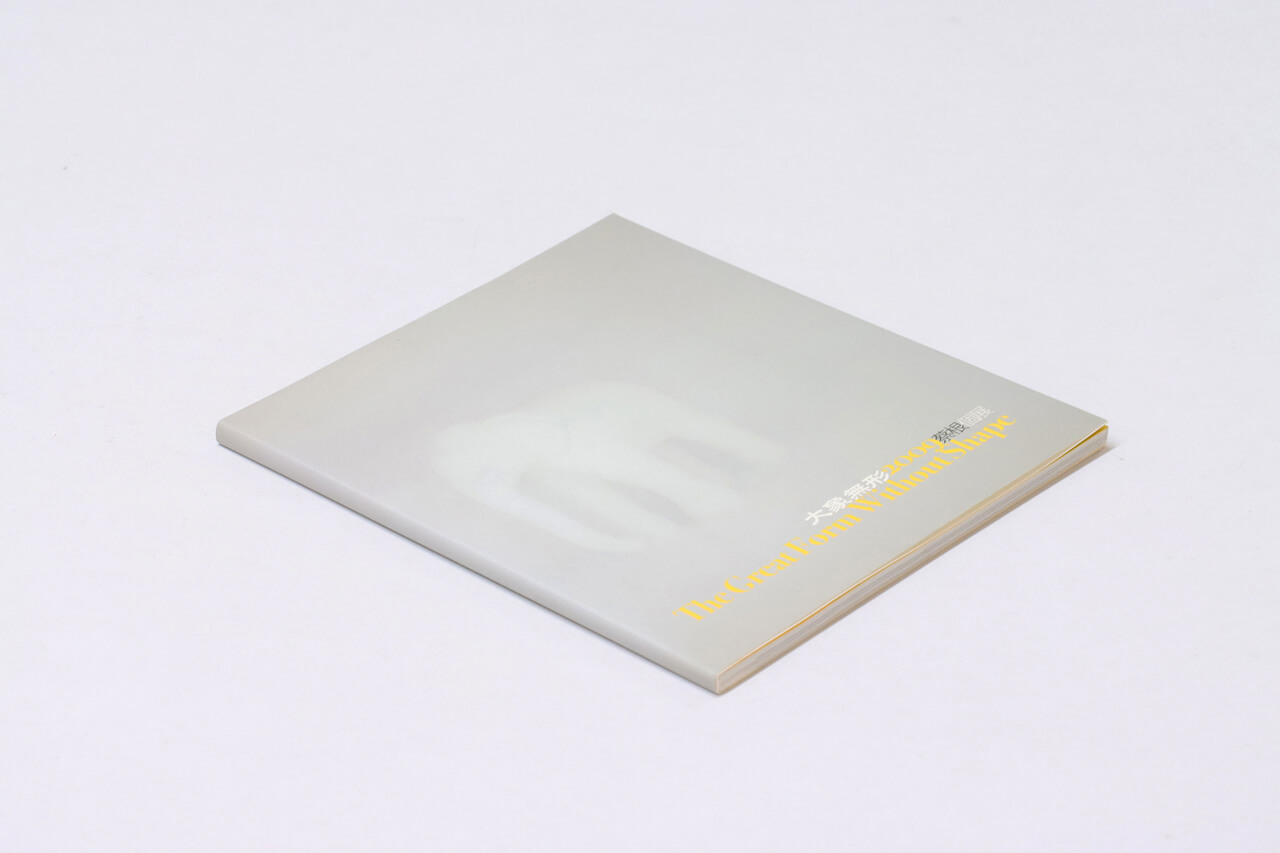

Reaching his middle age, Tsai resumed reading old classics written by Confucius, Mencius, Laozi, and Zhuangzi, whereby he had an epiphany about his life. Distinct from Western art concepts, “the great form without shape” by Laozi and “setting the mind at flight by going along with things as they are” by Zhuangzi represent an oriental thought that returns to one’s root self.

⌈Reading the sentence “the great form has no shape” in Laozi, I searched many annotated versions for comprehending its true meaning. I create works of visual arts, but I’ve always thought that an image reaches its zenith when it sends out a message and recedes into the background, leaving behind the chemical reaction catalyzed by the image-evoked feeling and the viewer’s mind.

Images are paramount in visual arts, yet they should do more things than to catch the viewer’s eye.

“The great form without shape” thus becomes an ambitious goal of my personal pursuit.

|Tsai Ken6⌋ |

⌈In my philosophy of life, all things stand in a relationship of reciprocal causation. I’ve been trying to prove it in my life. After four decades of artistic creation, I let go of techniques and forget all about craftsmanship, using only the combination of objects to embody this ideal.

This approach also echoes both Zhuangzi’s words: “setting the mind at flight by going along with things as they are” and my personal endeavor in demonstrating sincere convictions by utilizing readymade.

|Tsai Ken7⌋ |

|Tsai Ken, Garden on the Carpet (partial), 2019, 290x80x60cm, Mixed media

Tsai Ken, Garden on the Carpet, 2019, 290x80x60cm, Mixed media

|

Tsai staged his first solo exhibition when he approached 40. Then he continued to present his works on a biennial or triennial basis, thereby expressing his perception as well as the harmony and beauty of life. In the midst of many art waves, Tsai still retains his own creative vocabulary. Art critic Liao Ren-I commented:

⌈Tsai Ken is an artist who is able to hide his profound, delicate artistic thoughts beneath the surface of his sculptural works.

He is also an artist capable of grasping the ideological evolution from modern to contemporary sculpture, whilst continuing to explore his innermost self within his own line of thought.

|Liao Ren-I, Art Critic8⌋ |